Anxiety is such a fascinating topic and one that with each passing year I get more and more passionate about.

As a Somatic Educator working with dancers at The Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (and in the professional arena) for over 15 years it was only recently that I began working across the voice and music departments as well. When I made that shift I was immediately struck with how my knowledge slipped even more perfectly into this area, particularly for the voice students.

Evolutionarily the voice is one of our most precious assets for communication and, in times of need, protection. We whisper, laugh, cry, sing, gasp, shout and scream in relation to the needs of the moment.

As a singer, teacher or performer we use our voice to communicate each day and yet at times, our voice can fail us, particularly when the stakes are high, or when we’re so frightened or overwhelmed we literally cannot speak.

Everyone has a unique response to stress, anxiety and fright, which is essentially our response to danger or perceived danger. While speaking or singing may be one of our greatest loves, performing in front of a group of strangers can initially be an anxiety-inducing experience – biologically strangers are a threat!

Our physiological response to danger goes back to a primitive reflex called the Moro Reflex, which becomes our Adult Startle Reflex. This reflex goes on to underpin our fight, flight and freeze responses.

The Startle Reflex is elicited by 2 very specific stimuli:

-

A sudden loss of support (falling) and, interestingly for musicians

-

A sudden noise over 80 decibels (like speaker feedback!)

In response to danger, or perceived danger, our autonomic nervous system orchestrates a whole series of changes to our breathing, heart rate, muscle activation and vocalisation to meet the challenge of the moment and we experience our personal variations of the flight, fight and freeze responses.

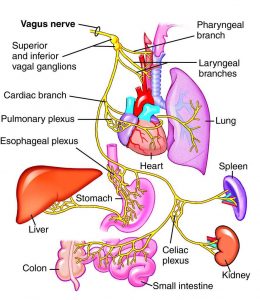

One of the major nerves to control these changes is the Vagus nerve or 10th Cranial nerve. It travels the longest distance of any nerve of the autonomic nervous system and extends to include the mouth, tongue, larynx, heart, lungs and digestive organs.

Just looking at that list you can see clearly how stress, anxiety and fright would have a profound affect on vocal performance.

The saying “I have a frog in my throat” relates to these physiological changes and while our biology may be assisting us to be ultra quiet (or ultra loud) in times of danger this is not helpful when the perceived danger is our joy – singing and speaking.

You may recognise some of these common experiences

-

Dry mouth

-

Rising pitch

-

Quickening speech/song

-

Tension or constriction of the vocal cords

-

Tension in the jaw and tongue

-

Lump/Frog in the throat

-

Raspy voice

-

Loss of breath

-

Quietening voice

-

Loss of voice entirely

Each one of these changes can be traced back to a biological purpose, but when it comes to singing and speaking, most of these do not assist!

To compound matters, unless you have developed your skills for optimizing performance under pressure, awareness of these physical changes can perpetuate the experience – your physiology confirming your anxiety – and an awful anxiety loop begins.

So having cast our attention briefly over the biology and physiology what are some simple things we can do to prepare for a great performance.

CONSIDER THE NOISES

- Take time to listen and get familiar with the unique noises of the venue

- Eliminate unnecessary noise where possible

- Make sure you are happy with your earpiece if you’re wearing one

- Check the volume and placement of the fallback speakers

- Take time out in a quiet place before the show

- Resist talking/listening to people who make you anxious

- If you notice a problem with sound ask the sound desk to adjust asap

SOOTH THE VOCAL APPARATUS

- Sip lukewarm drinks like herbal tea. (Some people prefer a cool drink but lukewarm drinks are more gentle on the cords. Alcohol is a natural relaxant but this is not always a good long-term choice.)

- Place a hand on your throat. Feel the warmth and softness of your hand. Take a few breaths like this.

- Place a pen lengthways in your mouth to stimulate the smile reflex, particularly if you now reflect on how silly you now look J

- Use the tongue to gently feel the inside of your gums, teeth and lips, as if tasting the remanent sweetness of a past dessert. Lick right around to the back of the teeth and over the lips too.

- Yawn, even if you fake it to start, to release the jaw and quieten the nervous system.

- Do a gentle lions tongue pose or hakka face, with the tongue hanging out fat and full.

- Make gentle soothing sounds like sighing, ahhhhing, hmmmming

Anxiety is a whole body/brain/mind experience and when we create change in one area we see changes in the whole experience. Pick one or two of the ideas above and see how they work for you.

If this kind of work interests you there are many wonderful Somatic Educators. Consider methods like Feldenkrais, Alexander Technique and Linklater and seek help from a practitioner who can give you specific homework. Practicing in the comfort of your home, without stress or anxiety, makes it much easier to access when you need it most! And if you feel that your experience of anxiety is particularly challenging seek out a Somatic Educator who specialises in anxiety.

If you would like to work specifically with me I have a private practice in West Perth and I provide Skype sessions for clients outside of Perth, WA.

And be sure to look out for my follow up article “Anxiety, Posture and Your Ability to Stay Grounded” in the coming months.

“Unless stated otherwise, this article represents only the views of the author and not the views of the AVA”

Molly Tipping is a Somatic Educator, Feldenkrais Practitioner and Pilates Instructor specialising in performance and anxiety. Molly has been working with performing artists for the over 15 years and currently runs a private practice in West Perth and lecturers at the West Australian Academy of Performing Arts (in the Dance and Music Departments). Molly also runs trainings for the Feldenkrais Guild of Australia, The Pilates Method Association and The Royal Academy of Dance and is the co-producer of Move Over Anxiety, an audio program currently on sale in Australia and The United States.